Decades of bad fishing practices have left our oceans in a tragic state. Many species which were once common-place are now threatened, dwindling to the point where there aren’t enough to catch and make a profit.

Over 90% of predatory species like cod and tuna have already been caught and, according to the UN, 70% of fisheries are overfished.

Numbers of fish are dropping faster than they can reproduce and this is causing profound changes to life in our oceans. In reality, there aren’t plenty more fish in the sea.

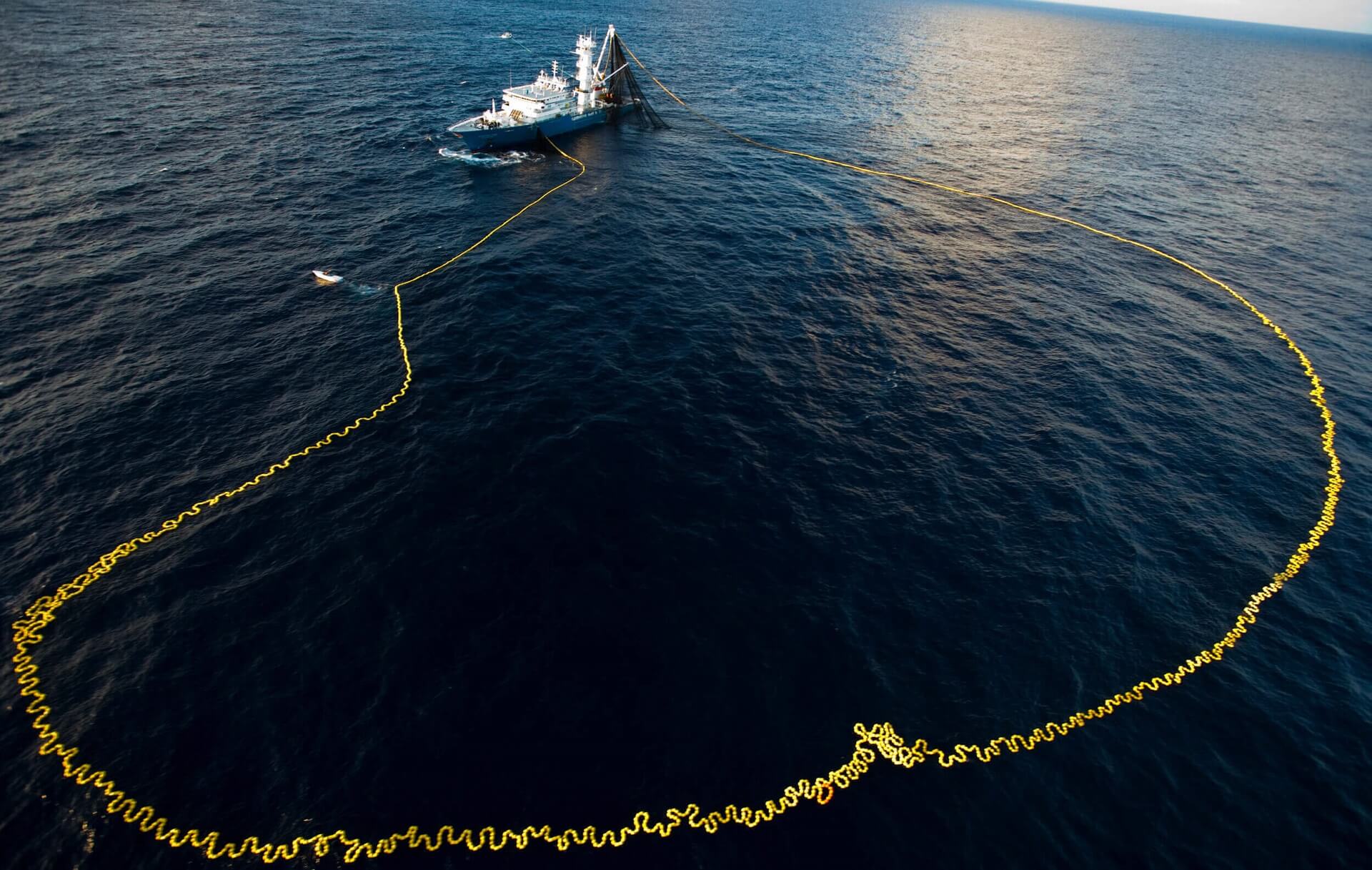

The fishing industry has become high-tech and giant ships use sonar to find fish schools with pinpoint accuracy. Huge nets catch fish in vast numbers. These ships are also floating factories, with processing and packing plants to handle their catch more efficiently. All this means there is now capacity to catch many times more fish than are actually left.

SOURCE: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/challenges/sustainable-fishing/

Overfishing is emptying the seas

As traditional species disappear, other species are targeted and even renamed to make them more appealing. For instance, the Patagonian toothfish was reinvented as the more appetisingly named Chilean seabass. Fleets are also venturing into more distant waters in the Arctic and Southern oceans to ravage fish populations there.

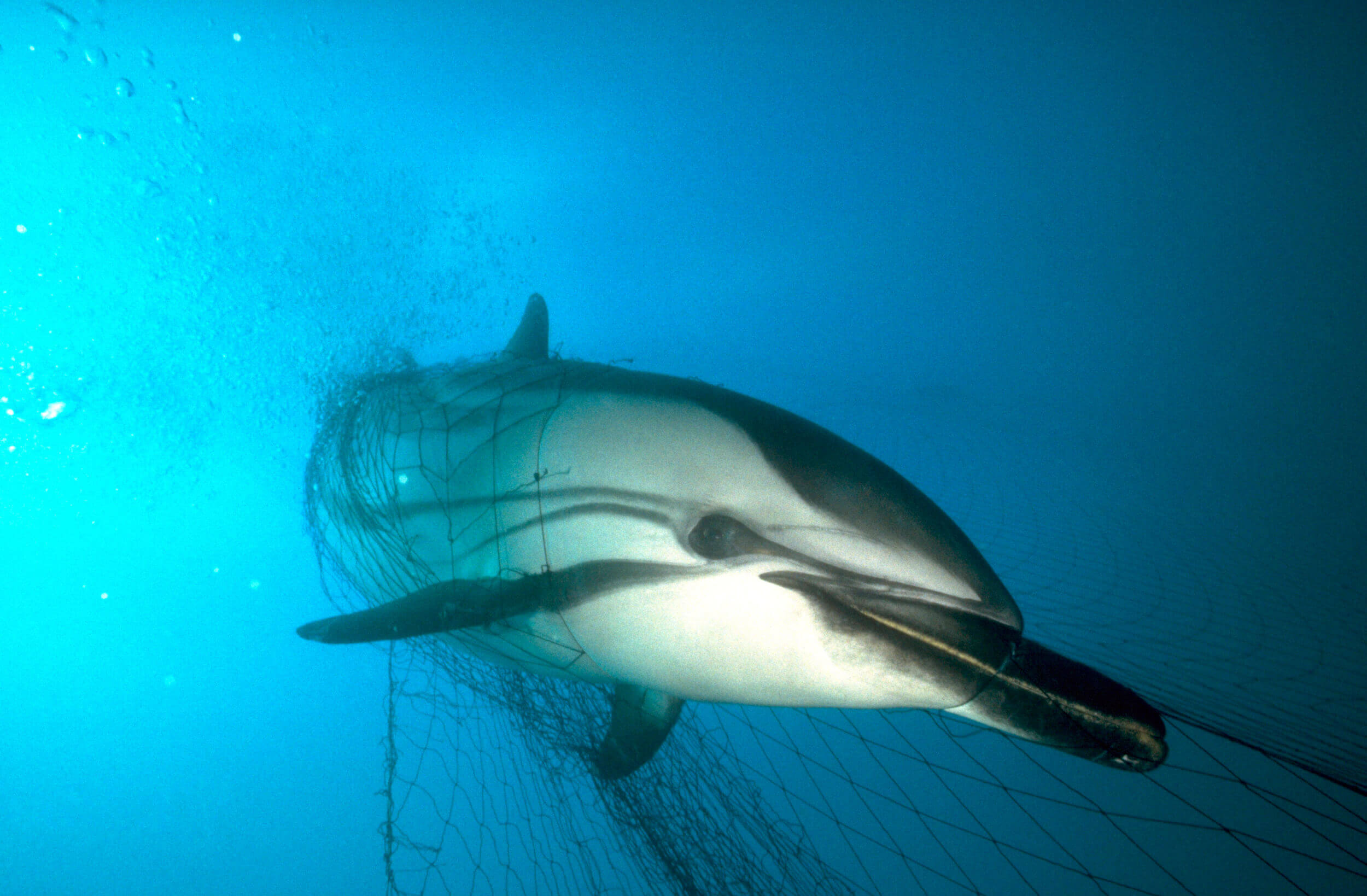

Fishing methods used by these ships are often very destructive. Bottom and beam trawling drag nets across the seabed to catch flat fish like hake and sole. But they also smash everything in their way, destroying fragile coral reefs. And most fishing methods are very indiscriminate, catching many other species by accident. This bycatch includes turtles, sharks, dolphins and other fish, which are often thrown back dead or dying into the sea.

There’s a human cost too. Industrial fishing means small-scale fishers using more traditional methods are suffering. In the UK, smaller boats are finding it hard to make enough money and communities in many fishing ports are economically deprived. The number of fishers has also halved in the last 20 years. Elsewhere in the world, people who depend on fish for food and income are seeing their stocks disappear as foreign vessels trawl in their waters.

Unfair fishing quotas

The way the UK government allocates fishing quotas plays a big part in this. Quotas have become concentrated in the hands of a small number of multi-million pound companies. Just five families control nearly a third of UK fishing quotas and more than two thirds of fishing quota is controlled by just 25 companies. Compared to smaller fishing operations, these big companies employ fewer people, use less sustainable fishing methods and less money makes its way into local economies.

Our government already has the power to change the way it distributes quotas. Greenpeace is campaigning for a fairer allocation system that favours local, sustainable fishing which will help create jobs and allow fish stocks to recover.

We’re also taking on the corporate giants plundering our oceans. Thai Union, the biggest tuna company in the world and owner of John West, was turning a blind eye to appalling conditions for workers and destructive fishing practices. But then an outcry from thousands of people around the world forced Thai Union to clean up its operations.

And we need to create more protected areas at sea. A network of ocean sanctuaries will provide refuges for fish and other marine life to thrive away from the threat of industrial fishing fleets. With climate change creating other threats to our oceans, we need to give them all the help we can.

In pictures: Sustainable fishing

An Indonesian crew member displays a turtle caught on the end of a bait line of a Korean longliner, the ‘Shin Yung 51’. The location is within the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Republic of Kiribati. Sharks, turtles, dolphins and albatrosses can often end up as unfortunate by-catch of longline fishing. Greenpeace are on the Pacific Leg of the ‘Defending Our Oceans’ global expedition. They are calling for an immediate end to pirate fishing, a 50% reduction in the amount of Pacific tuna caught, and a global network of Marine Reserves. Yellow Fin and Big Eye tuna stocks in the Central and Western Pacific are destined to be critically over-fished within three years if the relentless fishing of the two Tuna species continues at current rates. © Greenpeace / Alex Hofford

Striped dolphin caught in a French driftnet off the Azores, North Atlantic. © Greenpeace / Peter Rowlands

French artisanal fisherwoman catches a hake with a landing net. © Lagazeta / Greenpeace

A Vietnamese crew member releases a shark back into the ocean which was caught on the end of a bait line of a Korean longliner, the ‘Shin Yung 51’. whilst fishing for tuna. The location is within the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Republic of Kiribati. Sharks, turtles, dolphins and albatrosses can often end up as unfortunate by-catch of long-line fishing. Yellow Fin and Big Eye tuna stocks in the Central and Western Pacific are now drastically low due to pirate fishing and the over fishing of stocks by foreign, industrial nations. Local fishermen struggle to compete in these waters as sophisticated fishing equipment puts them out of business. Greenpeace are calling for an immediate end to pirate fishing, a 50% reduction in the amount of Pacific tuna caught, and a global network of Marine Reserves to tackle the problem of over fishing. © Greenpeace / Alex Hofford

Selected bycatch discarded from the deep sea trawler ‘Chang Xing’ in international waters in the Tasman Sea. Greenpeace along with more than a thousand scientists are supporting the call for a moratorium on high seas bottom trawling, because of the vast amount of marine life that is destroyed by this fishing method. © Greenpeace / Roger Grace

Tururuko, head of the local fishermen, directs the crew every day during fishing activities in Pemba, Quirimbas, northern Mozambique. © Francisco Rivotti

A team from the Greenpeace ship MV Esperanza documents discarded bycatch on the deck of a Spanish flagged bottom-trawler, the Ivan Nores, in the Hatton Bank area of the North Atlantic, 410 miles north-west of Ireland. Bottom-trawling boats, the majority from EU countries, drag fishing gear weighing several tonnes across the sea bed, destroying marine wildlife and devastating life on underwater mountains – or ‘seamounts’. © Greenpeace / Kate Davison

Schools of fish circle a fish aggregating device (FAD) in the Western Pacific Ocean. Around 10% of the catch generated by purse seine FAD fisheries is unwanted bycatch and includes endangered species of sharks and turtles. The catch of large amounts of juvenile bigeye and yellowfin tunas in these fisheries is now threatening the survival of these commercially valuable species. Greenpeace is calling for a total ban on the use of fish aggregation devices in purse seining and the establishment of a global network of marine reserves. © Paul Hilton / Greenpeace

Shamus Nicholls on his boat “Little Lauren” catching bass with a handliner. He is one of the fishermen that support sustainable fishing in small scale boats. © David Sandison / Greenpeace

Fishermen use pole and line fishing method to catch skipjack tuna. Pole and line fishing is a selective and therefore more sustainable way to catch tuna as only fish of a certain size are caught, leaving juveniles to grow to spawning age and replenish the stock in the future. Small bait fish are thrown over the side of the boat to lure the tuna to the water surface. The fishermen use the acceleration of the fish as they race to get their prey, hook them and fling them onto the ship’s flat deck. © Greenpeace / Paul Hilton

Spanish Albatun Tres is 115 mt long and is the world’s largest tuna purse seiner. Vessels such as this travel from one fish aggregation device (FAD) to another and spread their huge nets to catch everything swimming around the FAD. Around 10% of the catch generated by purse seine FAD fisheries is unwanted bycatch and includes endangered species of sharks and turtles. The catch of large amounts of juvenile bigeye and yellowfin tunas in these fisheries is now threatening the survival of these commercially valuable species. Greenpeace is calling for a total ban on the use of fish aggregation devices in purse seining and the establishment of a global network of marine reserves. © Paul Hilton / Greenpeace

The fishermen pull the skipjack tuna fish onto the boat in Flores sea, East Nusa Tenggara. The fishermen in Larantuka are famous for using sustainable methods, pole and line, on fishing tuna. Pole and line fishing is a traditional method of fishing, unchanged for generations, and often used by local fishers in coastal communities, using live bait, the fishing targets surface schooling skipjack. © Jurnasyanto Sukarno / Greenpeace

SOURCE: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/challenges/sustainab...